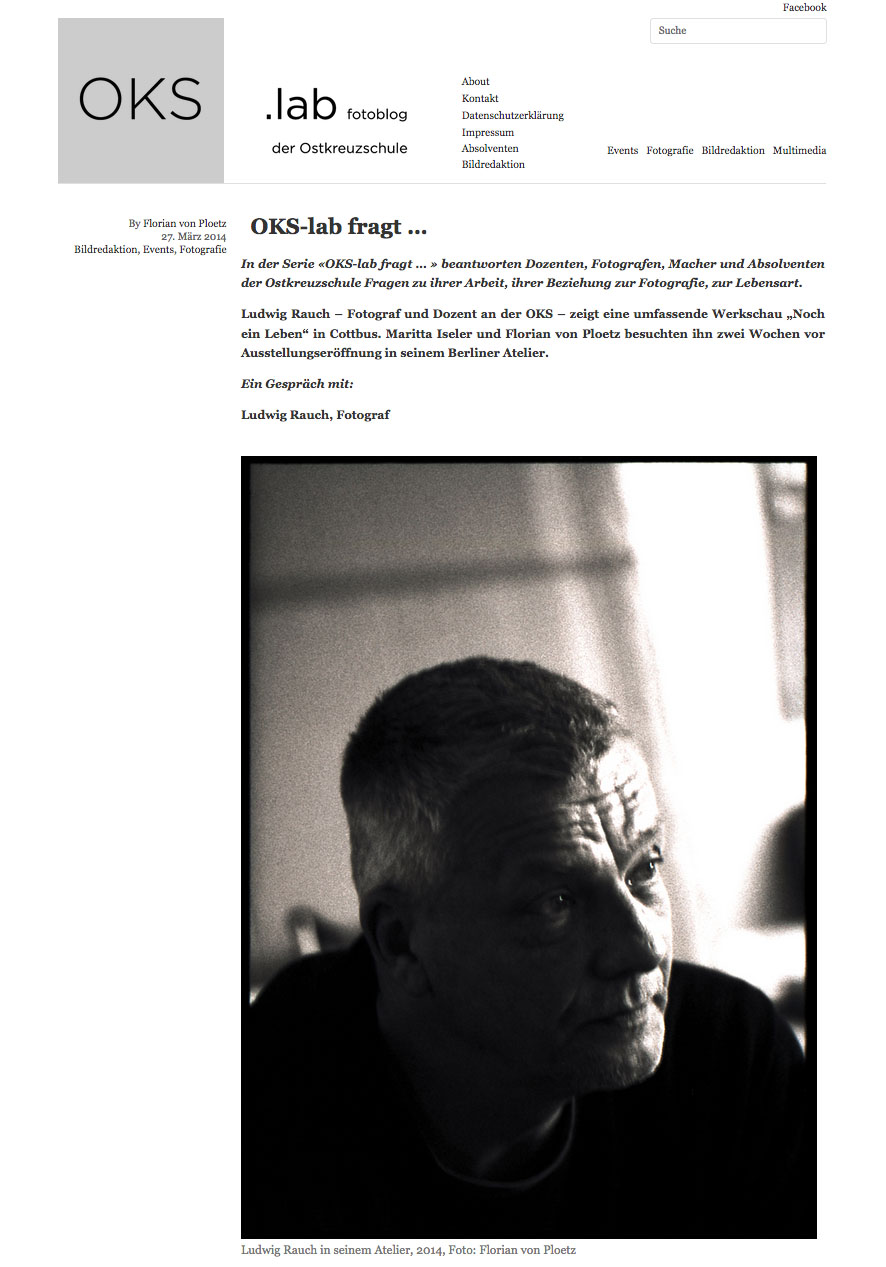

Rauch did not give up searching for this balance between extreme mood swings when, as a photographer, he said farewell to his own life as citizen. The “New Germany” (editorial note: „Neues Deutschland“ - socialist daily newspaper) that had disappeared, remaines in a deserted area at night. (p. ...). Everyone left, went missing, struck out on the road to somewhere else. Only the snowflakes are left untroubled. They trickle through the dismay with gentle poetry. It is the evening before his departure to the west.

All these images are thanks to a stir of emotion that need not be that of the observer, but still is not easily dismissed in pleasing agreement with a shot of schnapps. Even so, if the fall of the Wall made world history, Rauch’s images surpass the limits of reporting on events because they crystallize the motif in contrasts and organize a powerfully composed tracking of the eyes. Thus, in the rush to the West, a border officer is washed over by a wave of people in flight, as if by the inflamed hopes of a delirious nightmare (p. ...). The glimmers of unfocused movement on the surface, which show the image of a whirl of excited people, flow from this onto a guard who wants to be at the centre of events. His illuminated forehead is the only part of the image that, in the decisive moment of a global rupture, stayed sharp, even motionless. The photography of a rite of initiation in Marrakech comes from another continent and, as a photographic event, from another epoch. The connection with the image of the fall of the Wall arises solely from the vision of the photographer, who here too focuses on a single point, a single actor, in the chaotic, incalculable throng of excited people. It is the figure of father and son on the towering gray horse. They seem to float in the line of sight of the observer while pushing a swath of light in front of them; they arrange the storm from light to dark, like a musical score. The precision of the choreography of the image develops, in both cases, an inner narrative that transcends the outer, motif-lending narrative.

In such crisp images the world shines out, yet as a fragment of the self-perception of the photographer, who, so to speak, creates traces of his life’s journey on the road. At the same time, he chronicles events that would remain unbeheld were they not elevated into a pictorial event. The images therefore frame and capture not simply the overlooked, those things that an attentive eye should view carefully because otherwise no one would. Rather, they seek in the moment the event that defines the era, to give it a countenance.